Unit Testing

(If you have already signed up) Read the moodle first

The Moodle pages of the course contain important information which you should read before studying these pages, including information about the aims of the project and its grading. The moodle pages also link to the most relevant parts of these pages. These pages expect you to be familiar with the contents of the moodle and can feel confusing if you are not.

These instructions are strongly based on the course Software Production Unittest Guidelines.

Let’s explore unit testing using the unittest framework. In unit tests, the focus is on testing the smallest structural components of a program, such as individual functions, class objects, and their methods.

As an example, we will use the PaymentCard class, which includes methods for loading balance and purchasing meals of different values:

# Meal prices in cents

AFFORDABLE = 250

DELICIOUS = 400

class PaymentCard:

def __init__(self, balance):

# Balance in cents

self.balance = balance

def eat_affordably(self):

if self.balance >= AFFORDABLE:

self.balance -= AFFORDABLE

def eat_deliciously(self):

if self.balance >= DELICIOUS:

self.balance -= DELICIOUS

def load_money(self, amount):

if amount < 0:

return

self.balance += amount

if self.balance > 15000:

self.balance = 15000

def __str__(self):

balance_in_euros = round(self.balance / 100, 2)

return "The payment card has {:0.2f} euros".format(balance_in_euros)

NOTE: All monetary values, such as the balance on the payment card and meal prices, are in cents.

We will go through one way to test this class using Poetry, unittest, and pytest.

Initial Setup

First, create a directory named paymentcard, and within it, run the following command in the terminal to initialize the project:

poetry init --python "^3.10"

The details that Poetry asks for regarding the project are not important, so you can accept the default values suggested by Poetry.

Next, install the pytest framework as a development dependency to simplify test execution. This can be done within the same directory using the following command:

poetry add pytest --group dev

Next, let’s create the following structure within the paymentcard directory:

paymentcard/

src/

paymentcard.py

tests/

__init__.py

paymentcard.py

...

Then, add the previously introduced PaymentCard class code into the src/paymentcard.py file.

Now, let’s try to run the tests. Enter the virtual environment using the command poetry shell, and then run the command pytest src. If no tests are executed, it’s because we haven’t implemented any tests yet.

Let’s implement our first test in the src/tests/paymentcard_test.py file. The content of the file should look like this:

import unittest

from paymentcard import PaymentCard

class TestPaymentCard(unittest.TestCase):

def setUp(self):

print("Set up goes here")

def test_hello_world(self):

self.assertEqual("Hello world", "Hello world")

After running the command pytest src again within the virtual environment, you will notice that one test has been successfully executed. Keep in mind that the src argument after the pytest command limits the search for tests to the src directory located in the root directory of the project. If no argument is provided, pytest will search for tests directly in the root directory of the project.

The pytest src command looks for executable tests in the src directory of the project and recursively in all of its subdirectories. For pytest to know which tests to execute, proper naming conventions must be followed. These conventions are:

- Test file names must end with the suffix _test, e.g., paymentcard_test.py

- The name of the test class must start with the Test prefix, e.g.,

TestPaymentCard - The name of the test class methods must start with the test_ prefix, e.g.,

test_hello_world

Note that the test directory must contain an empty init.py file for Python to identify the modules properly. Without this file, the test would fail with the following error:

ModuleNotFoundError: No module named 'paymentcard'

If there are subdirectories within the test directory, they should also contain an empty init.py file.

Next, let’s create the first meaningful test, which checks if the constructor of the PaymentCard class correctly sets the balance:

import unittest

from paymentcard import PaymentCard

class TestPaymentCard(unittest.TestCase):

def setUp(self):

print("Set up goes here")

def test_constructor_sets_correct_balance(self):

# Initialize a payment card with 10 euros (1000 cents)

card = PaymentCard(1000)

result = str(card)

self.assertEqual(result, "The payment card has 10.00 euros")

The first line initializes a card with a balance of 10 euros. The purpose of the test is to ensure that the value passed as a parameter to the constructor is set as the card’s initial balance. This is verified by checking the card’s balance. The card’s balance is obtained from the string representation of the card, created by its __str__ method. The second line of the test creates a string representation of the card object and stores it in the result variable. The last line checks whether the result matches the expected result, which is “The payment card has 10.00 euros”.

The verification is done using the assert statement, which is commonly used in unittest. The statement checks if the expected result (given as the first parameter) is the same as the actual result (given as the second parameter in the test). There are various assert methods available.

Next, let’s run the test using the command pytest src and hope it passes.

An alternative way to define the same test would be as follows:

def test_constructor_sets_correct_balance(self):

card = PaymentCard(1000)

self.assertEqual(str(card), "The payment card has 10.00 euros")

In this case, the value returned by the method call is not stored in a separate variable but is directly called within the assertEqual comparison. This works because before the actual comparison is made, the function call is executed, and its returned value is used for the comparison.

It’s important to ensure that the test truly catches errors. So, let’s modify the previous test so that it doesn’t pass (by claiming in assertEqual that the balance is 9 euros):

def test_constructor_sets_correct_balance(self):

card = PaymentCard(1000)

self.assertEqual(str(card), "The payment card has 9.00 euros")

Running the tests will indicate that the test was not executed successfully. Each failed test will provide a detailed explanation of the cause of the issue. Additionally, at the end, it will list the failed files and methods in a more compact form:

FAILED src/tests/paymentcard_test.py::TestPaymentCard::test_constructor_sets_correct_balance -

AssertionError: 'The payment card has 9.00 euros' != 'The payment card has 10.00 euros'

Next, let’s create a test to ensure that the card’s balance decreases correctly when calling the eat_affordably method:

def test_eat_affordably_decreases_balance_correctly(self):

card = PaymentCard(1000)

card.eat_affordably()

self.assertEqual(str(card), "The payment card has 7.50 euros")

The test starts again with creating a card. Next, the method to be tested is called, and lastly, there is a line that ensures the result is as expected, meaning that the card balance has decreased by the price of the affordable meal.

A few notes

Both tests are simple and test only one thing, which is a recommended practice even though it is possible to include multiple assertEqual method calls in a single test. The tests are named so that the name clearly indicates what the test is verifying. Additionally, it is always important to use the test_ prefix in the method name. All tests are independent of each other; for example, paying with a card does not affect the card balance except in the test where the card payment occurs. The order of the tests in the test code does not matter. Tests should be run as frequently as possible, i.e., every time you write a test (or modify regular code), run the tests!

Our tests are a little inconvenient in that they test the change in the payment card’s state through the string representation of the card. We could also design the test so that it directly checks the value of the balance attribute from the payment card object to ensure the correct value after the meal payment:

def test_eat_affordably_decreases_balance_correctly_2(self):

card = PaymentCard(1000)

card.eat_affordably()

# ensure that the remaining balance is 7.5 euros, i.e., 750 cents

self.assertEqual(card.balance, 750)

This is somewhat inconvenient because we can think that the way the card stores the balance in cents is an internal matter, which the developer who implemented the card may later change.

So, let’s add a new method balance_in_euros to the card, which allows checking the card’s balance in euros:

class PaymentCard:

# ...

def balance_in_euros(self):

return self.balance / 100

Let’s modify the test to use the new method:

def test_eat_affordably_decreases_balance_correctly_2(self):

card = PaymentCard(1000)

card.eat_affordably()

self.assertEqual(card.balance_in_euros(), 7.5)

Additional Tests

Now, let’s add two more tests:

def test_eat_deliciously_decreases_balance_correctly(self):

card = PaymentCard(1000)

card.eat_deliciously()

self.assertEqual(card.balance_in_euros(), 6.0)

def test_eat_affordably_does_not_allow_balance_to_go_negative(self):

card = PaymentCard(200)

card.eat_affordably()

self.assertEqual(card.balance_in_euros(), 2.0)

The first test checks that eating the delicious meal correctly decreases the balance. The second test ensures that you cannot buy the affordable meal if the card balance is too low.

Test Setup

We notice repetition in our test code: all the first three tests create a card with a balance of 10 euros.

So we will move the method creation to the initialization method defined in the test class, setUp.

class TestPaymentCard(unittest.TestCase):

def setUp(self):

self.card = PaymentCard(1000)

def test_constructor_sets_correct_balance(self):

self.assertEqual(str(self.card), "The payment card has 10.00 euros")

def test_eat_affordably_decreases_balance_correctly(self):

self.card.eat_affordably()

self.assertEqual(self.card.balance_in_euros(), 7.5)

def test_eat_deliciously_decreases_balance_correctly(self):

self.card.eat_deliciously()

self.assertEqual(self.card.saldo_euroina(), 6.0)

def test_eat_affordably_does_not_allow_balance_to_go_negative(self):

card = PaymentCard(200)

card.eat_affordably()

self.assertEqual(self.card.balance_in_euros), 2.0)

The setUp method is executed before each test case (i.e., each test method). This means that every test case gets access to a PaymentCard object with a balance of 10 euros. Note that the payment card being tested is stored in the test class’s instance variable using the line self.card = PaymentCard(1000). This ensures that the test methods can access the payment card created by the setUp method.

Test methods can still initialize objects for different use cases, as in the test method test_eat_affordably_does_not_allow_balance_to_go_negative. Note that in this case, self.card refers to the instance variable initialized in the setUp method, whereas card refers to a local variable within the method.

Additional Tests

Let’s create a test for the load_money method. The first test ensures that loading money is successful, and the second test verifies that the card’s balance does not exceed 150 euros.

def test_loading_money_completed_successfully(self):

self.card.load_money(2500)

self.assertEqual(str(self.kortti), "The payment card has 35.00 euros")

def test_balance_not_over_maximum(self):

self.card.load_money(20000)

self.assertEqual(str(self.card), "The payment card has 150.00 euros")

Tests Are Independent of Each Other

As mentioned earlier, tests are independent, meaning that each test functions as a standalone small function. But what does this really mean?

The PaymentCard is tested with multiple small test methods, each starting with the prefix test_. Each individual test checks a specific aspect, such as whether the card’s balance decreases by the price of a meal. The key idea is that every test starts with a “clean slate,” meaning that before each test, a new card is created in the setUp method.

Every test begins with a freshly created card. The test then either calls the method under test directly or first sets up the necessary preconditions before making the call. This approach was used in test_eat_affordably_does_not_allow_balance_to_go_negative, where a separate PaymentCard with insufficient balance was initialized to verify that purchasing a discounted meal does not result in a negative balance.

The Complete Test Class

import unittest

from paymentcard import PaymentCard

class TestPaymentCard(unittest.TestCase):

def setUp(self):

self.card = PaymentCard(1000)

def test_constructor_sets_correct_balance(self):

self.assertEqual(str(self.card), "The payment card has 10.00 euros")

def test_eat_affordably_decreases_balance_correctly(self):

self.card.eat_affordably()

self.assertEqual(self.card.balance_in_euros(), 7.5)

def test_eat_deliciously_decreases_balance_correctly(self):

self.card.eat_deliciously()

self.assertEqual(self.card.balance_in_euros(), 6.0)

def test_eat_affordably_does_not_allow_balance_to_go_negative(self):

card = PaymentCard(200)

card.eat_affordably()

self.assertEqual(card.balance_in_euros(), 2.0)

def test_loading_money_completed_successfully(self):

self.card.load_money(2500)

self.assertEqual(self.card.balance_in_euros(), 35.0)

def test_balance_not_over_maximum(self):

self.card.load_money(20000)

self.assertEqual(self.card.balance_in_euros(), 150.0)

Have We Tested Enough? Test Coverage

We are satisfied and believe that we have written enough test cases. But is this really the case? Fortunately, there are tools available to check both line and branch coverage.

- Line coverage measures which lines of code have been executed during testing. While 100% line coverage does not guarantee that the program is error-free, it is better than having no coverage at all.

- Branch coverage measures which execution branches have been traversed. Execution branches include, for example, different cases of

ifconditions.

Since branch coverage typically provides a more realistic assessment of test completeness, we will use it as the primary metric for test coverage in this course.

Test Coverage Report

Test coverage can be collected using the coverage tool. Installing it as a development dependency for the project is done using the following command:

poetry add coverage --group dev

Collecting test coverage from tests executed with pytest src can be done within a virtual environment using the following command:

coverage run --branch -m pytest src

With the --branch flag, we can collect branch coverage, which tracks which decision points (such as if statements) have been tested.

Note that the pytest src command limits test discovery to the src directory in the project’s root.

After running the coverage command, we can print a report of the collected test coverage with:

coverage report -m

The output will look something like this:

Name Stmts Miss Branch BrPart Cover Missing

---------------------------------------------------------------------------

src/paymentcard.py 22 1 8 2 90% 15->exit, 20

src/tests/__init__.py 0 0 0 0 100%

src/tests/paymentcard_test.py 23 0 0 0 100%

---------------------------------------------------------------------------

TOTAL 45 1 8 2 94%

Excluding Files from the Coverage Report

From the output, we can see that there are many files included in the report that are unnecessary for the project. We can configure which files should be included in the coverage report by modifying the .coveragerc file in the project’s root directory.

If we want to include only the src directory in the coverage report, the configuration should look like this:

[run]

source = src

We can also exclude files and directories from the coverage report. For example, it might be sensible to exclude the test directory, the UI code directory, and the src/index.py file. This can be achieved with the following changes to the .coveragerc file:

[run]

source = src

omit = src/**/__init__.py,src/tests/**,src/ui/**,src/index.py

Now, running the commands coverage run --branch -m pytest src and coverage report -m will include only the desired files from the src directory:

Name Stmts Miss Branch BrPart Cover Missing

----------------------------------------------------------------

src/maksukortti.py 22 1 8 2 90% 15->exit, 20

----------------------------------------------------------------

TOTAL 22 1 8 2 90%

A More Visual Test Coverage Report

To generate a clearer, more visual representation of the test coverage, you can run the following command:

coverage html

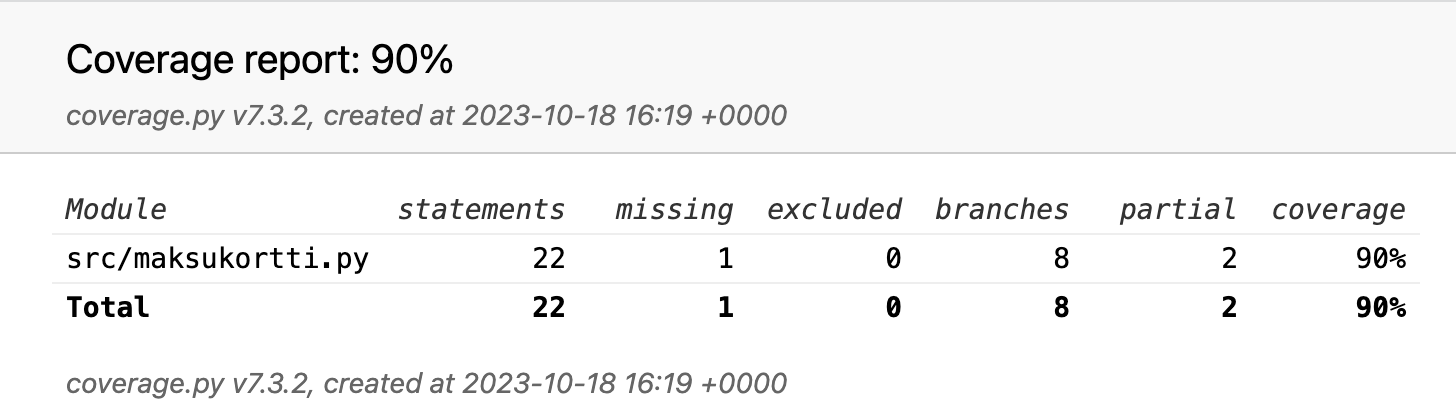

Executing this command creates a new directory called _htmlcov_ in the project’s root directory. You can view the report by opening the index.html file within this folder in a browser. The report will look something like this:

From the report, we can see that the overall branch coverage of the code is 90%. The “coverage” column in the table shows the branch coverage for individual files. Clicking on a file name in the table will open the file’s code and highlight the branches that are covered by tests. Covered branches are indicated by green bars next to the line numbers. Branches that are not covered at all are highlighted in red. If a branch is partially covered, it will be highlighted in yellow. Hovering over a line will provide more detailed information about why the branch is not fully covered:

In the situation of the image, the two if-conditions never received the value

In the situation of the image, the two if-conditions never received the value True, so those branches were not handled in the tests.

After the code changes, two commands need to be executed in the new test coverage determination. You can execute both commands “with one click” by placing them on the same line separated by a semicolon.

coverage run --branch -m pytest src; coverage html

Note on Testing Larger Projects

It is important to note that in the subdirectories of the src directory (not in the src directory itself), there must be empty __init__.py files in order for all the desired files to be included in the test coverage. For example, in the case of the course Software Engineering reference application, the __init__.py files have been added as follows:

src/

entities/

__init__.py

todo.py

...

repositories/

__init__.py

todo_repository.py

...

services/

__init__.py

todo_service.py

...

Fix This Page

Make an suggestion for an improvement by editing this file in GitHub.